In the previous post, we established the benefits of Offline RL. But why offline RL is not widely used yet?

Based on my experience in Autonomous Vehicle and LLM and my limited exposure to robotics, I can argue that offline RL is practically not used (autonomous vehicle companies mostly use BC, GAIL, and Online RL, LLM uses BC and Online RL, Board Games - AlphaGo, AlphaZero, and MuZero uses Model Based RL and MCTS, Robotic OpenVLA, Pi policies uses BC and Online RL). In fact we can argue that most of the current real-world successes of RL have been achieved with variant of on-policy RL algorithms (e.g., REINFORCE, PPO, GRPO) which require fresh, newly sampled rollouts from the current policy or slightly older policy, and cannot reuse old data. This is not a problem in some settings like board games and LLMs, where we can cheaply generate as many rollouts as we want. However, it is a significant limitation in most real-world problems. For example, in autonomous vehicles and robotics, it takes more than several months in the real world to generate the amount of samples used to post-train a language model with RL. Yet, Offline RL hasn’t been used, why?

We can categorize the challenges with offline RL in two main categories:

- Practical Challenges

- Core Technical Challenges

Practical Challenges:

Engineering, Scalability, Complexity, and the Human factor

Offline RL training algorithms requires a significant amount of memory and training of multiple network simultaneously (e.g. multiple critics, target critics, policies, behavior models (generators), and/or ensembles) and requires at least 2x the wall-clock time compare to BC. While this works for small policy models, it makes it hard to adopt for large models. One of the appeal of GRPO and RLOO is that they forgo the need for value model which make LLM RL training feasible and faster.

Offline RL often depend on implementation-level details (architecture tweaks, state normalization, entropy removal, action sampling strategy) that are not always part of the algorithm’s mathematical core and requires more effort to tweak and tune.

RL in general is less well understood and less popular compared to Behavior Cloning and given that in the last 15 years most of the attention was on: scaling, self supervised learning, and representation learning engineers tend to leverage techniques that are better understood.

Those issues while seem to be superficial should not be underestimated, team and companies prefer methods that are fast, stable and easy to tweak so they can iterate quicker.

Offline to Online (O2O)

Offline RL alone rarely achieves optimal performance—the policy is fundamentally limited by the quality and coverage of the static dataset. In practice, practitioners want to use offline RL as initialization, then fine-tune with online interaction to surpass the dataset's limitations. This makes the offline-to-online transition critical. Unfortunately, this transition is often harder than simply fine-tuning after behavior cloning.

- Distribution shift and value function collapse. Policies trained offline learn from a fixed dataset. When they begin interacting with the environment online, they inevitably encounter states and actions outside that dataset. Value functions trained offline can be wildly inaccurate in these unfamiliar regions—sometimes outputting arbitrary or even adversarial values—leading to poor or catastrophic performance during the transition.

- Pessimism-optimism tension. Offline RL methods succeed by being pessimistic: they undervalue uncertain or out-of-distribution actions to avoid overestimation. But online RL requires optimism (or at least willingness to explore) to discover better strategies. Naively switching from one regime to the other causes a sharp performance drop—sometimes called the "dip"—as the agent unlearns its conservative behavior before acquiring enough online experience to compensate.

- Catastrophic forgetting of offline knowledge. When online fine-tuning begins, the agent can quickly overwrite what it learned offline, losing useful behaviors before gathering enough online data to replace them. Balancing retention of offline knowledge with online adaptation remains an open problem.

Reward specification and annotation burden

Offline RL requires a reward signal for every transition (s,a,r,s′) in the dataset (or every episode). For many real-world domains, these rewards simply don't exist. When an autonomous vehicle records a driving trajectory or a robot logs a manipulation episode, the system captures states and actions—but not a dense reward signal indicating how "good" each moment was.

This creates a significant annotation burden. Practitioners must either:

- Engineer a reward function post-hoc, mapping logged signals (distances, collisions, task completion) to scalar rewards—a process that's error-prone and often produces reward hacking.

- Manually annotate trajectories with human judgments, which is expensive and doesn't scale.

- Use Inverse RL to infer rewards from demonstrations, which adds algorithmic complexity and its own failure modes.

Behavior cloning sidesteps this entirely: it only requires demonstrations of desired behavior, with no reward labels needed. This "reward-free" property is a major practical advantage that's easy to overlook when comparing methods on benchmarks where rewards are provided by default.

GAIL sidesteps explicit reward engineering by framing reward as a discrimination problem—learning to distinguish expert behavior from non-expert—though this introduces its own training instabilities.

Core Technical Challenges:

Bootstrapping error accumulation and long-horizon scaling

Many offline RL methods rely on Q-learning. In Q-learning the value \(Q(s,a)\) effectively represents the sum of rewards into the infinite future. For a task with an effective horizon \(H \approx \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\), a single Bellman update only propagates information one step backward in time. To learn the value of the start state from the reward at the goal state, information must successfully propagate through \(H\) recursive updates.

In standard Q-learning (TD Learning)

$$\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(s,a,r,s') \sim \mathcal{D}} \left[ \left( Q_\theta(s,a) - \left(r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q_{\theta'}(s', a')\right) \right)^2 \right]$$

The bias accumulates linearly with each recursive step. Since the value function magnitude itself scales with \(H\), the worst-case error bound for the value function scales quadratically.

This quadratic scaling (\(H^2\)) is a significant problem for long-horizon tasks. For an autonomous vehicle driving task or robotic task with a horizon of 500 steps, the bias multiplier is on the order of 250,000. Even if massive datasets reduce the single-step error \(\epsilon\) significantly, the \(H^2\) term magnifies the remaining microscopic bias until it overwhelms the signal. This explains why simply "scaling up" Offline RL with more data and larger models often yields diminishing returns or failure, whereas BC continues to improve.

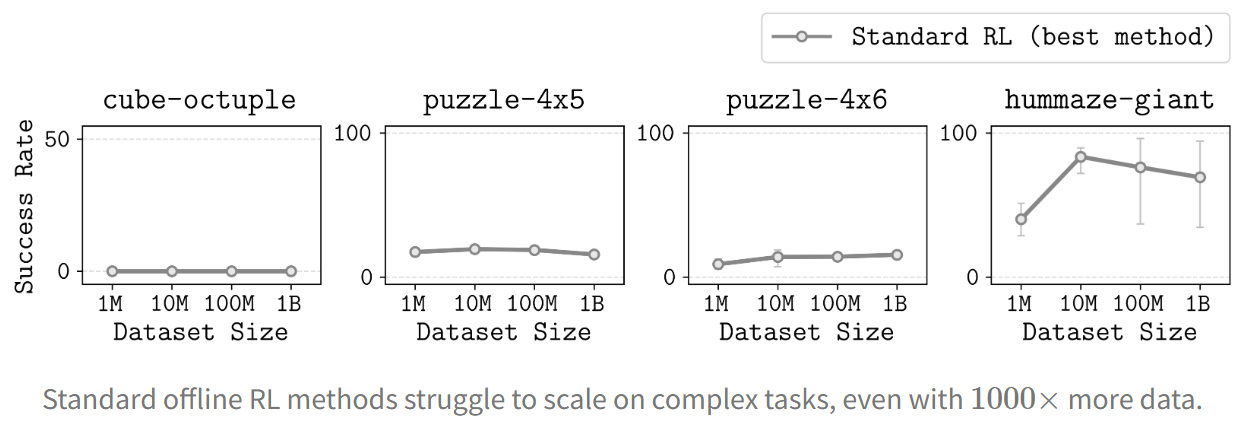

Practitioners observe that Offline RL works on short-horizon "toy" tasks (like HalfCheetah, Ant-Maze) but fails on complex, multi-stage robotic tasks where \(H\) is large. Even with huge amounts of data, empirical studies showed that current offline RL methods don’t scale or even improve.

Given these challenges—engineering overhead, harder offline-to-online transitions, reward annotation burdens, and fundamental scaling limits—it's no surprise that practitioners default to simpler alternatives. In Part 3, we'll examine recent advances that aim to address these issues and ask whether offline RL's moment may finally be approaching.